During my teaching, translation and proofreading career, I’ve noticed that many translation students and even professional translators don't have a strong background in syntax. Or, being too focused on improving their language grammar, they neglect the study of syntax or don’t know the difference between grammar and syntax. This is a big disadvantage in the translation profession and industry because syntax is one of our strongest tools we have as linguists.

Syntax is too often overlooked in translation studies, and contrastive syntax is usually non-existent. So I thought I could fill up that gap a little bit by writing this blog post and ultimately creating a workshop on contrastive syntax.

Contrastive Syntax is the study of syntax that compares how two languages order words in different ways, side by side. It is the study of syntax reloaded, especially useful for translators, linguists or language students. But let’s rewind and define syntax first.

According to linguistic professor Andrew Carnie, syntax is the scientific study of sentence structure. Syntax dictates the rules for how a language is structured. Words and phrases can’t be placed in any which way if we want to convey meaning. If we break syntactic rules, we can break communication, create ambiguities, introduce errors or write poetry.

While grammar gives you the rules for language use, syntax gives you the rules for how to structure language.

So for now, there are two points that should be standing out when we define syntax: a scientific study and language structure.

You probably never thought of language as scientific, but I’ll show you how syntax is a scientific method of reading, analyzing, and creating language—everything we translators do every day while at work.

Science works with a particular method. The scientific method is an empirical method of acquiring knowledge that involves a set of steps. The first one is to observe data or ask a question. Based on that question, a generalization is made, and a testable explanation is put forward, also known as hypothesis. After you have a hypothesis, you set out to test it with experiments. While testing, you analyze your findings and confirm your hypothesis, or if not possible, you revise or refine it. You repeat this process until your hypothesis is confirmed.

So let’s apply the scientific method to syntax in English, and then contrast it to syntax in Spanish. Let’s do contrastive syntax.

First, let’s define two main types of sentences in any language. One is declarative statements and the other is yes/no questions.

A declarative sentence asserts that an event or state of affairs has occurred, or hasn’t or will or won’t. A yes/no question is a question that can be answered by yes/no (or maybe). The same definitions apply to the Spanish enunciado declarativo and interrogativas totales, respectively.

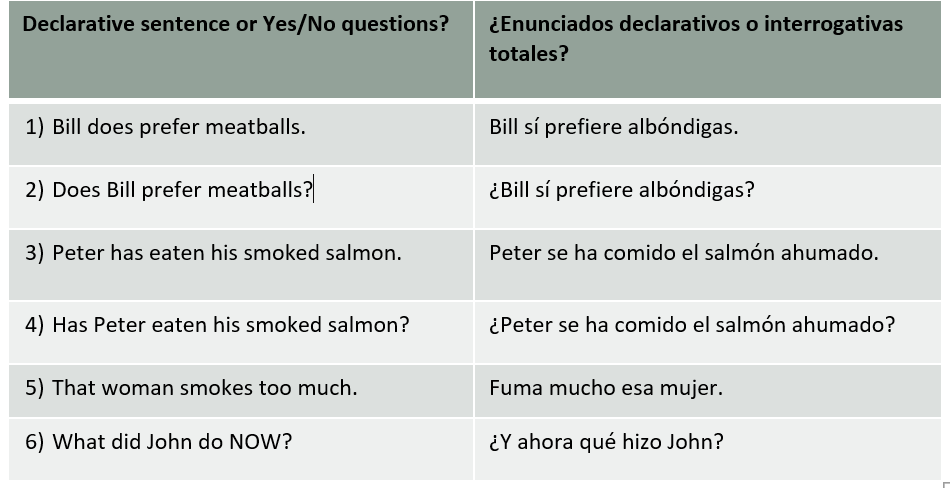

Let’s now begin our scientific method by observing a few declarative sentences and yes/no questions in a contrastive table, comparing English and Spanish examples.

In the chart, we have three declarative sentences, #1, #3 and #5; two yes/no questions, #2 and #4, derived from their equivalent declarative sentences; and one final wh-question, #5.

I’m going to concentrate on the yes/no questions.

By observing these yes/no questions and their equivalent declarative sentences, we can hypothesize how yes/no questions are formed, that is, their syntactic definition.

In English yes/no questions are formed by moving the second word of the declarative statement to the front.

Bill does prefer meatballs.

Does Bill prefer meatballs?

Peter has eaten his smoked salmon.

Has Peter eaten his smoked salmon?

These examples corroborate our hypothesis.

Let’s now propose a syntactic definition of Spanish interrogativas totales.

In Spanish yes/no questions are formed using the same order as in the declarative sentences and adding opening and closing question marks.

Bill sí prefiere albóndigas.

¿Bill sí prefiere albóndigas?

Peter se ha comido el salmón ahumado.

¿Peter se ha comido el salmón ahumado?

The examples also corroborate our hypothesis. But two examples are too few to draw conclusions. Let’s put it to a further test.

Based on these additional examples, our first hypothesis in English—moving the second word of the declarative statement to the front—doesn’t hold.

Frodo ate the magic beans.

Ate Frodo the magic beans?

The little hobbit will eat the magic beans.

Little the hobbit will eat the magic beans?

The result is an incoherent, ungrammatical sentence. So we’ll have to refine our first hypothesis as:

In English yes/no questions are formed by moving the AUXILIARY derived from a verb in the declarative sentence to the front, followed by the subject and the infinitive verb, and then the rest of the information.

Frodo ate the magic beans.

Did Frodo eat the magic beans?

The little hobbit will eat the magic beans.

Will the little hobbit eat the magic beans?

The hypothesis has been proven.

Let’s now turn to some of our Spanish examples:

Frodo se comió las habichuelas mágicas.

¿Se comió Frodo las habichuelas mágicas?

El pequeño hobbit se va a comer las habichuelas mágicas.

¿Se va a comer las habichuelas mágicas el pequeño hobbit?

¿Las habichuelas mágicas se las va a comer el pequeño hobbit?

Based on these additional examples, our first hypothesis in Spanish—using the same order as in the declarative sentences and adding opening and closing question marks—doesn’t cover some of these examples. So we’ll have to refine our first hypothesis as:

In Spanish yes/no questions are formed using the SAME OR DIFFERENT order as in the declarative sentences and adding opening and closing question marks.

It checks out.

But because the scientific method is all about iteration, why don’t we add one more complex sentence and test this last hypothesis?

Our hypothesis in English stated that:

In English yes/no questions are formed by moving the AUXILIARY derived from a verb in the declarative sentence to the front, followed by the subject and the infinitive verb, and then the rest of the information.

So let’s test it with the new example.

The hobbit who danced at the party has eaten the magic beans.

We find the first verb: danced. Its auxiliary is DID, which we move it to the front, add the subject, the hobbit, and infinitive verb, dance, and then complete the question with the rest of the information:

Did the hobbit dance at the party has eaten the magic beans?

Or

Did the hobbit dance at the party who has eaten the magic beans?

Both results are ungrammatical and incoherent. The second hypothesis in English doesn’t hold, and needs to be refined as:

Yes/no questions are formed by moving the AUXILIARY derived from the verb in the MAIN CLAUSE of the declarative sentence to the front, followed by the subject and the infinitive verb, and then the rest of the information.

The hobbit who danced at the party has eaten the magic beans.

The main verb in this declarative sentence is has eaten. The auxiliary is has, which we move to the front. Then we find the main subject and add the infinitive verb, followed by the rest of the information, but in a hierarchical way.

Has the hobbit who danced at the party eaten the magic beans?

I’ll explain what I mean by hierarchical way in a minute, but first let turn our attention to the Spanish original declarative sentence, and create as many yes/no questions as possible.

El hobbit que bailó en la fiesta se ha comido las habichuelas mágicas.

1) ¿El hobbit que bailó en la fiesta se ha comido las habichuelas mágicas?

2) ¿Se ha comido las habichuelas mágicas el hobbit que bailó en la fiesta?

3) ¿Las habichuelas mágicas se las comió el hobbit que bailó en la fiesta?

4) ¿Bailó en la fiesta el hobbit que se ha comido las habichuelas mágicas?

Our previous hypothesis in Spanish stated:

In Spanish yes/no questions are formed using the SAME OR DIFFERENT order as in the declarative sentences and adding opening and closing question marks.

While this is still consistent with the examples, we moved the elements so much that we introduced a change in example #3. The change in syntax resulted in a change in emphasis. The declarative sentence and first two yes/no questions put the emphasis on the hobbit. The yes/no question #3 puts the emphasis on the magic beans. This is just one simple example of what syntax can do. It can emphasize something, but it can also introduce ambiguity, humor, poetry... and inconspicuous errors.

So our revised Spanish hypothesis can now read:

In Spanish yes/no questions are formed using a VERY FLEXIBLE order that can match or not that of the declarative sentence and give different degrees of emphasis. They are opened and closed by interrogation marks.

Now about the hierarchical order that I promised earlier. Both the English and Spanish declarative sentences and derived yes/no questions have a hierarchical sequence that, when we move it, can create ungrammatical sentences, a different emphasis or a completely different meaning.

Let’s move some elements around and see what happens:

1. The hobbit who danced at the party has eaten the magic beans. >> ORIGINAL DECLARATIVE SENTENCE

2. The hobbit has eaten the magic beans. >> INFORMATION ABOUT THE HOBBIT REMOVED

3. The hobbit danced at the party who has eaten the magic beans. >> UNGRAMMATICAL

4. The hobbit danced at the party and has eaten the magic beans. >> RETAINED ORIGINAL INFO, BUT CHANGE IN SYNTAX WITH LIKELY CHANGE IN EMPHASIS

5. Has the hobbit who danced at the party eaten the magic beans? >> ORIGINAL YES/NO QUESTION

6. Did the hobbit who’s eaten the magic beans dance at the party? >> YES/NO QUESTION WITH A CHANGE IN SYNTAX, MEANING AND EMPHASIS

1. El hobbit que bailó en la fiesta se ha comido las habichuelas mágicas. >> ORIGINAL DECLARATIVE SENTENCE

2. El hobbit se ha comido las habichuelas mágicas. >> INFORMATION ABOUT THE HOBBIT REMOVED

3. El hobbit bailó en la fiesta que se ha comido las habichuelas mágicas. >> UNGRAMMATICAL

4. El hobbit bailó en la fiesta y se ha comido las habichuelas mágicas. >> RETAINED ORIGINAL INFO, BUT CHANGE IN SYNTAX WITH LIKELY CHANGE IN EMPHASIS

5. ¿Se ha comido las habichuelas mágicas el hobbit que bailó en la fiesta? >> ORIGINAL YES/NO QUESTION

6. ¿El hobbit que bailó en la fiesta se ha comido las habichuelas mágicas? >> ORIGINAL YES/NO QUESTION WITH CHANGE IN SYNTAX, NO CHANGE IN EMPHASIS

7. ¿Las habichuelas mágicas se las comió el hobbit que bailó en la fiesta? >> YES/NO QUESTION WITH A CHANGE IN SYNTAX AND EMPHASIS

8. ¿El hobbit que se comió las habichuelas bailó en la fiesta? >> YES/NO QUESTION WITH A CHANGE IN SYNTAX, MEANING AND EMPHASIS

This is the power of syntax. Just by changing the order, we’re conveying different things. What makes this possible is the concept of constituencies.

A constituent is a sequence of words that functions together as a unit within the hierarchy of a sentence. This the most important and basic notion in the study of syntax. Constituents can’t be placed in any which way. They are embedded one inside another to form the hierarchical structure of a sentence.

For example, in

The hobbit who danced at the party has eaten the magic beans.

who danced at the party is related to the hobbit, and therefore embedded in the whole subject.

The hobbit who danced at the party is the whole subject that is doing the main action, eating.

All the constituents in our original declarative sentence are highlighted in different colors below:

And in a more complex sentence:

If you can distinguish each constituent in the sentences you read, translate and write, you’ll be able to understand them more deeply, see embedded emphasis, meanings and ambiguities and then transfer the intended ones into your target language, without introducing undetected errors.

Language is not structured linearly, but hierarchically. That is one of the reasons we don’t translate word by word, or use the same word order as the original text.

The meaning of a sentence is not simply the sum of its linear elements. Every sentence has a hierarchical structure that gives a particular meaning to each word in relation to its surrounding context.

If you’re interested in learning more about syntax and delving into a linguistic discovery, join me in my next workshop, Contrastive Syntax for Translators – English < > Spanish. You can find more info here.

references

Carnie, Andrew. Modern Syntax: A Coursebook. Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Di Tullio, Ángela. Manual de Gramática del español. Edicial, 1997.